There is a curious thing about human nature that we should rather look away from uncomfortable truths than face them squarely. We prefer our religion sanitised, our theology tidied up, our symbols cleaned and made respectable. This tendency, I think, explains why so many of our Protestant brethren have such an aversion to the crucifix—that ancient Christian symbol which depicts our Lord not merely upon a cross, but suffering upon it, dying upon it, with all the uncomfortable particulars of the Passion laid bare before our eyes.

“Give us the empty cross,” they say, “for Christ is risen!” And risen He most certainly is—but this preference reveals, I suspect, something rather telling about our spiritual squeamishness. We should like to skip from Palm Sunday directly to Easter morning, bypassing entirely that dreadful business of Good Friday. Rather like schoolchildren who wish to jump from the exciting beginning of a story straight to the happy ending, leaving out all the difficult bits in between.

But Christianity is not a religion for those who wish to avoid difficult bits. Indeed, if we are honest, the entire business is one difficult bit after another, punctuated by moments of extraordinary grace. The crucifix forces us to confront two truths simultaneously—truths so profound and so terrible that we can scarcely bear to look upon them, yet so essential that without them Christianity becomes merely another pleasant moral philosophy.

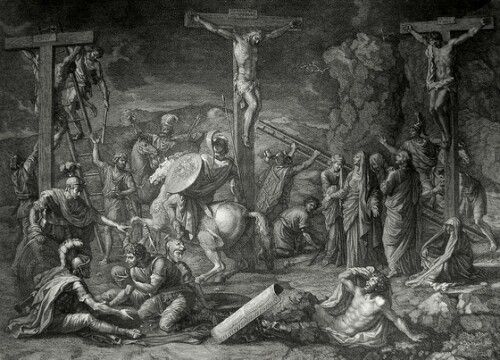

The Scandal of the Cross

The first truth is what we might call the scandal of the cross: the full weight of human sinfulness displayed in all its ugly particularity. When we gaze upon the crucifix, we see not merely a good man unjustly executed (though He was that), nor simply a martyr dying for his principles (though He was that too), but something far more disturbing. We see ourselves.

For it was not merely the Romans who crucified Christ, nor only the Jewish authorities of His day. Every lie we have told, every act of selfishness, every moment when we have chosen our own will over God’s—all of this contributed to the weight that pressed down upon those wounded shoulders. As the ancient hymn puts it, “Who was the guilty? Who brought this upon Thee? Alas, my treason, Jesus, hath undone Thee!”

Saint Augustine understood this when he wrote, “It was pride that changed angels into devils; it is humility that makes men as angels.” The cross is the great mirror held up to human pride, showing us precisely where our rebellion against the Almighty leads. Not to the glorious independence we imagined, but to the torture of an innocent man—and not just any man, but the very Son of God.

This is why the empty cross, for all its beauty and truth, cannot tell the complete story. The empty cross speaks of victory—and rightly so—but the crucifix speaks of cost. It reminds us that this victory was not achieved by some cosmic sleight of hand, some divine magic trick that made everything right again with a wave of the Almighty’s hand. No, it was purchased with blood, with agony, with the cry of dereliction that echoes still across the centuries: “My God, my God, why hast Thou forsaken me?”

We modern Christians, I fear, have grown far too comfortable with the idea of cheap grace—that wonderful phrase coined by Dietrich Bonhoeffer. We should like to be forgiven without truly understanding what our forgiveness cost. We should prefer to think of God as a kindly grandfather who overlooks our little pecadilloes with an indulgent smile, rather than as the Holy One whose justice demanded satisfaction and whose love provided it at such a price.

The crucifix will not allow us this comfortable delusion. It forces us to confront the horrible mathematics of sin and redemption: that every petty cruelty, every moment of pride, every act of selfishness had to be paid for, and that the currency in which this debt was settled was nothing less than the life-blood of the Word made flesh.

The Love Beyond Measure

But the crucifix speaks not only of our sin; it speaks equally—and perhaps more loudly—of God’s love. Here we encounter the second truth, no less overwhelming than the first: that the same cross which displays the horror of human sinfulness displays also the incomprehensible depth of divine love.

“Greater love hath no man than this,” said our Lord, “that a man lay down his life for his friends.” But what sort of love is this that lays down its life not merely for friends, but for enemies? Not for the worthy, but for the unworthy? Not for those who deserve it, but precisely for those who deserve the opposite?

Saint John Chrysostom, that golden-mouthed preacher of Constantinople, captured this paradox beautifully: “What madness is this? He who is worshipped by angels allows himself to be crucified by men!” Indeed, what madness—or what love so profound that it appears as madness to our finite understanding?

The empty cross, again, speaks truly of God’s power—the power that rolled away the stone and conquered death itself. But the crucifix speaks of something perhaps even more wonderful: God’s weakness. Not weakness in the sense of inability, but weakness in the sense of vulnerability chosen freely out of love. The Creator of the universe, who could have called down twelve legions of angels, instead chose to hang defenceless upon a tree.

This is the love that the crucifix proclaims: not the love that keeps us at a comfortable distance, not the love that helps us only when we deserve it, but the love that enters fully into our condition, takes upon itself all our sin and shame, and transforms even death itself into the instrument of redemption.

The Necessity of Both Truths

Now, some will say that this emphasis upon the crucifix is morbid, that it focuses too much upon death rather than life, upon suffering rather than joy. But this misses the point entirely. The crucifix is not morbid any more than a medicine is morbid for focusing upon disease. It is rather like a physician’s diagnosis—unflinchingly honest about the seriousness of the condition, but given always in the service of healing.

The truth is that we cannot properly understand the Resurrection without first understanding the Crucifixion. The empty tomb has meaning precisely because we know what happened to fill it in the first place. The joy of Easter morning is real joy precisely because it follows the genuine sorrow of Good Friday. As G.K. Chesterton observed, “Joy, which was the small publicity of the pagan, is the gigantic secret of the Christian.”

But this joy is not the shallow optimism of those who have never looked deeply into the darkness. It is rather the joy of those who have seen the very worst and discovered that even the worst is not beyond the reach of God’s redemptive love. It is the joy not of those who have avoided the cross, but of those who have found Christ upon it.

Saint Teresa of Avila understood this when she prayed, “Let me suffer or let me die”—not because she was morbidly fascinated with pain, but because she recognised that it is precisely in suffering that we are most closely united with our crucified Lord. The crucifix reminds us that the path to glory leads through Calvary, that there is no crown without a cross.

A Challenge to Comfortable Christianity

Perhaps this is why the crucifix makes us uncomfortable. It challenges our desire for a comfortable Christianity, a faith that costs us nothing and demands nothing difficult. The crucifix is not merely a historical artefact but a spiritual map. ‘Take up your cross and follow Me,’ said Christ. He did not say, ‘Admire the empty tomb’ but rather He planted us firmly in the present moment with that most mysterious yet essential element of our salvation: suffering. Following Christ is not a matter of adding a religious dimension to an otherwise unchanged life, but of imitating His path through suffering. The crucifix challenges us to imitate, not merely to adore.

The empty cross speaks of Christ’s victory, and rightly so. But the crucifix speaks of our calling to share in that victory through sharing in His sufferings. It reminds us that we are called not merely to benefit from the Atonement, but to participate in it—to “fill up what is lacking in Christ’s afflictions,” as Saint Paul mysteriously puts it.

This is not to say that we add anything to Christ’s perfect sacrifice—God forbid! But rather that His perfect sacrifice calls forth from us a response, a willingness to take seriously both the horror of sin and the costliness of grace. The crucifix calls us to what we might term “serious Christianity”—faith that has looked squarely at both human sinfulness and divine love and found itself changed by the encounter.

In the end, both symbols—the crucifix and the empty cross—tell essential parts of the Christian story. But in our age of easy religion and comfortable faith, perhaps it is the crucifix we most need to contemplate. For it alone forces us to confront the two truths that stand at the very heart of Christianity: that we are far worse than we ever dared imagine, and that God’s love for us is far greater than we ever dared hope.

Until we have truly grasped both truths—until we have seen ourselves clearly in the mirror of the cross and seen God’s love clearly in the wounds of Christ—we have not yet begun to understand what Christianity is about. The crucifix, uncomfortable though it may be, is thus not merely permissible but necessary. It is the visual gospel, the carved sermon, the wordless proclamation of the central mystery of our faith: that God so loved the world that He gave His only begotten Son.

And until we can look upon that giving without flinching, until we can see both the cost and the love it represents, we remain spiritual children, wanting the sweets of religion without the medicine, the crown without the cross, the comfort without the challenge.

The crucifix will not permit us this evasion. It stands as Christianity’s permanent reminder that the way to life leads through death, that the path to glory passes through shame, and that the love of God is proved not by what it spares us, but by what it was willing to endure for us.