I. Introduction: Manichaeism – A Universal Religion of Cosmic Despair

Manichaeism represents one of the most intellectually sophisticated and historically impactful challenges to the nascent Catholic faith. Founded in the third century AD by the Parthian Iranian prophet Mani (c. 216–274) in the Sasanian Empire, it quickly established itself as a major world religion. While sometimes described by its opponents as a Gnostic movement or a Christian heresy, Manichaeism was an organised, doctrinal tradition in its own right, characterised by vast geographical reach, thriving between the third and seventh centuries and briefly rivaling early Christianity in the West.

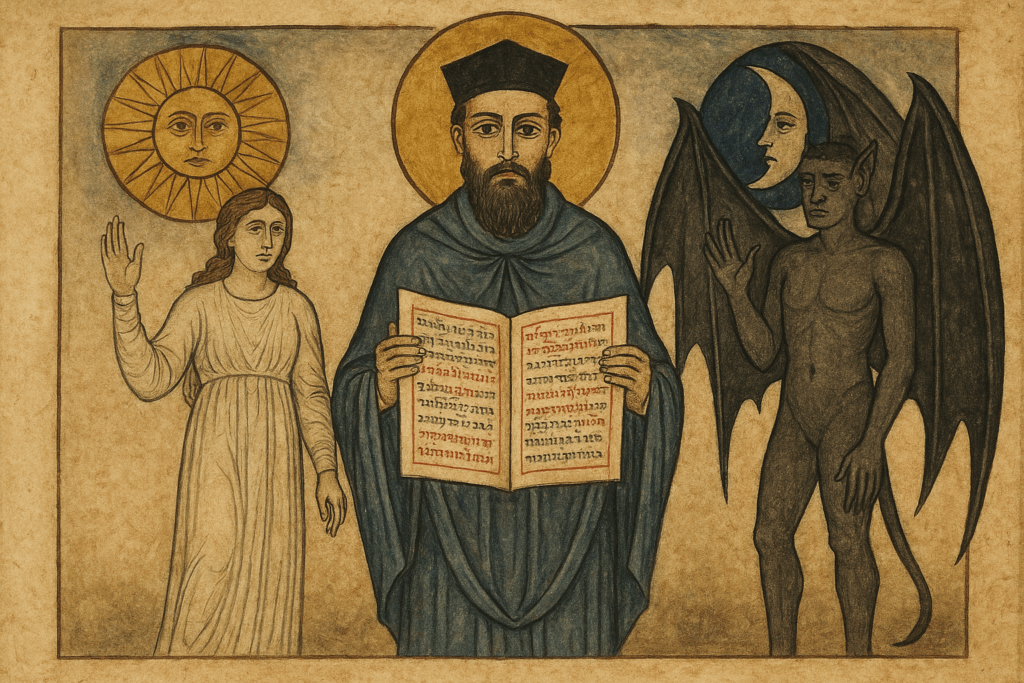

The intellectual framework of Manichaeism was fundamentally syncretic. Its cosmology synthesised elements from Mesopotamian religious movements, Buddhist ethics, Zoroastrian Dualism, Babylonian folklore, and superficial additions of Christian elements. This comprehensive approach was essential to Mani’s mission. He viewed himself as the “Apostle of Light” and the final successor in a long line of prophets, including Zoroaster, Gautama Buddha, and Jesus, aiming for his own teachings to integrate, succeed, and surpass all prior traditions. Mani even specifically proclaimed himself to be the Paraclete promised by Jesus, though he demonstrated a show of humility by styling himself the “Apostle of Jesus Christ by the providence of God the Father,” a designation adapted directly from the headings of the Pauline Epistles. This direct claim to authority and universal truth made the movement a potent theological threat, challenging the finality of Christ’s revelation and the unique role of the Holy Spirit in the Church.

The Defining Dualism: Light and Darkness

The core doctrine of Manichaeism rested on an elaborate radical dualistic cosmology. This theology posits an eternal, uncreated struggle between two distinct, co-equal, and antagonistic principles: a good, spiritual world of Light and an evil, material world of Darkness. The cosmos, including the present world, was viewed as a battleground where these two forces had become disastrously mixed. Matter, by its very nature, was associated with the forces of darkness, ignorance, and evil, while spirit was linked to goodness, knowledge, and the divine realm.

Within this cosmology, human souls were conceived as fragments of light trapped in the material world, which was itself seen as a creation of the evil force. The entire purpose of Manichaean ethical and cosmological schemes was the ongoing process of liberating these light particles from the cycle of reincarnation and returning them to the world of the divine, whence they came.

This metaphysical framework offered immense explanatory power to a generation grappling with profound human suffering and moral contradiction. Manichaeism provided a deceptively simplistic, yet compelling, solution to the perennial philosophical dilemma known as the Problem of Evil (theodicy). If an omnipotent and benevolent God is the sole creator of all existence (Theistic Monism), how is the existence of profound evil accounted for? By positing Evil (Darkness/Matter) as an external, uncreated, co-equal substance, the Manichaean system avoids the need to blame the good God for the world’s imperfections and suffering. This clear-cut, ontological separation of good and evil provided substantial intellectual comfort, fueling Manichaeism’s rapid expansion and allowing it to briefly function as the main rival to early Christianity.

II. The Pivotal Conflict: St. Augustine and the Birth of Catholic Metaphysics

The ultimate theological refutation of Manichaeism, and indeed the development of classical Catholic metaphysics concerning evil, is inseparable from the personal and intellectual journey of St. Augustine of Hippo. For nine formative years, Augustine was a devoted adherent to the Manichaean sect. His intellectual bondage to dualism stemmed initially from a difficulty shared by many ancient thinkers: an inability to imagine any substance other than such as is seen with the bodily eyes. The Manichaean explanation, which posited two rival, material kingdoms of Light and Darkness, gave him a structured way to conceptualise the forces governing existence.

The Comfort of Externalised Sin

During his time within the sect, Augustine found a certain psychological relief in its dualism. He later reflected in his Confessions that his sin was all the more incurable because he did not think himself a sinner; instead, he concluded, “it was all my own self, and my own impiety had divided me against myself”. This phrase highlights the profound moral consequence of Manichaean thought: it allowed Augustine to externalise the source of sin. If the evil he committed was a result of contamination by the eternal, evil material substance of Darkness, then he himself was not responsible, but rather a victim of a cosmic mistake. This displacement of moral responsibility represented a fundamental departure from biblical teaching on sin as a willful act against God’s law, and it was a critical error he needed to overcome for true conversion.

The ultimate breaking point in Augustine’s reliance on Manichaeism was not a spiritual crisis alone, but a philosophical one. He had long awaited a meeting with Faustus, the highly regarded Manichaean bishop. However, when the meeting occurred, Faustus, though charming and articulate, “could not answer Augustine’s metaphysical and epistemological objections to Manichaeism”. Augustine came to realise that the system, despite its sweeping cosmic claims, possessed deep philosophical flaws and was unworthy of his deepest intellectual commitment.

The Polemical Crucible of Orthodoxy

Augustine’s eventual conversion was a complex process involving his philosophical disillusionment, the Neo-Platonic concept of the spiritual nature of God, and finally, a profound moment of grace prompted by the reading of St. Paul’s Epistle to the Romans (13:13-14), leading to his baptism by St. Ambrose in 387 .

The intellectual struggle that followed defined Augustine’s theological trajectory and, by extension, that of Western Catholic thought. He became the Church’s most ardent and effective anti-Manichaean polemicist, dedicating numerous foundational works, including Seven Writings Against the Manichæan Heresy and the extensive Reply to Faustus the Manichaean. Augustine’s work in this period shows a deliberate strategy: refuting the radical dualism while modifying and strengthening the nascent Nicene faith where it was most vulnerable to Manichaean critique.

This intellectual confrontation with Manichaeism functioned as the single most critical event in solidifying the Catholic understanding of God and creation. Augustine’s detailed engagement forced the Church to move beyond simple pastoral affirmations to develop a rigorous philosophical defense of Theistic Monism, the doctrine that God is the sole sovereign being. This necessity, imposed by the coherence of the heresy, resulted in the enduring theological precision that distinguishes Catholic dogma.

Furthermore, Augustine’s transition from the Manichaean externalisation of evil to the Catholic definition of sin as a result of a defect in the will, rather than contamination by external matter, restored the fundamental biblical reality of human moral freedom and responsibility. This theological development laid the essential groundwork for his later defenses of divine grace and human free will in his subsequent polemical battles against the Pelagian heresy, demonstrating the essential interconnection of the ancient debates. The heresy, in a profound paradox, served as the whetstone upon which Catholic orthodoxy was sharpened.

III. The Ontological Abyss: Evil as Substance vs. Evil as Privation (Privatio Boni)

The chasm separating Catholic theology from Manichaeism is fundamentally ontological, revolving around the nature of existence and the origin of evil. Manichaeism, as a form of religious Dualism, insists that evil is a primary, positive, and substantial entity. It postulates two eternally opposed and coexisting principles, Light and Darkness, making the material world inherently corrupt. This view directly results in the Manichaean critique that creation is flawed and that God has alienated himself from it.

The Catholic Affirmation: Monism and the Goodness of Being

In contrast, Catholic teaching maintains Theistic Monism: there is one, supreme, omnipotent God who created all things ex nihilo (out of nothing). Consequently, the tradition affirms that everything that exists as a being or substance is fundamentally good. The material creation, the physical world, is not a regrettable mistake but a deliberate act of divine goodness, as affirmed repeatedly in Genesis (“God saw that it was good”). The condemnation of the Manichaeans specifically pointed out their error in alienating the creation from the Creator, arguing that the divine providence extends even to “the earth sprout[ing] vegetation” and the “waters bring[ing] forth moving creatures with living souls,” confirming that all visible things are God’s good creatures.

The Doctrine of Privatio Boni

The Catholic solution to the problem of evil is rooted in the doctrine of privatio boni, the privation or absence of a good that ought to be present. Following St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas, this theology posits that evil is not a substance (ens) but a deficiency (defectus). It is parasitic non-being. Moral evil is understood as a consequence of the misuse of free will by created beings, while physical evil results from the necessary limitations inherent in finite created substances.

Augustine captured this metaphysical point by explaining that evil is a privation of good, which gradually diminishes a thing until it ceases altogether to exist. He clarified that evil is not a substance; rather, a disease is an “accident, i.e., a privation of that good which is called health”. When a cure occurs, the defects are not transferred elsewhere; they simply cease to exist, confirming that evil has no intrinsic positive reality of its own.

This definition is crucial because it fully preserves God’s absolute goodness and sovereignty. If evil were a positive substance, God would either be the Creator of an eternal, independent evil principle (violating His goodness) or be limited by an existing evil force (violating His omnipotence). By defining evil as a lack or defect, Catholic theology ensures that God remains the sole source of all being and goodness.

The Paradox of Personal Evil

A common philosophical objection to the privatio boni theory, one that Augustine himself had to resolve, concerns the existence of personal, active evil agents, such as Satan. How can an intelligent, spiritual agent, whose existence is affirmed as ontological and historical by the Church, act through what metaphysically does not exist (a privation)?.

The resolution to this apparent contradiction rests on distinguishing the agent’s existence (substance) from the agent’s actions (defect). Satan, as a fallen angel, still exists as a spiritual creature, and as a substance created by God, he is ontologically good. His existence is real. However, his malice, temptation, and rebellion, what is categorised as his evil, are the absence or deficiency of the moral good (perfect love, obedience, rectitude) that he, as a rational creature, ought to possess. The evil is parasitic upon his good, created existence. The agent is real; the evil is the defect in the agent’s will. This nuanced understanding prevents the return to Manichaean dualism while acknowledging the terrible reality of personal spiritual warfare.

Key Ontological Differences: Heresy vs. Orthodoxy

The fundamental differences can be summarised by examining the core principles of each system:

- First Principle(s): Manichaean Dualism posits two co-eternal, opposed Principles (Light and Darkness), whereas Catholic Monism affirms one omnipotent, eternal God (Being, Pure Act).

- Origin of Evil: Manichaeism teaches that evil is a positive, eternal substance or entity (Matter). Catholic Orthodoxy defines evil as a privatio boni (privation of good), meaning it is a parasitic non-being or defect.

- Status of Matter: For Manichaeans, matter is inherently evil, created by the Principle of Darkness. The Catholic position is that matter was created ex nihilo by God and is, therefore, inherently good (Genesis 1).

- Source of Redemption: Manichaeans seek redemption through Gnosis (Knowledge) to separate Light from Matter. Catholic theology locates the source of redemption in Grace, achieved through the Incarnation and the Sacraments.

IV. Christological Heresy: The Incarnation and the Dignity of Matter

The metaphysical rejection of matter by the Manichaeans necessarily led to profound errors in Christology, forcing the Church to define the Incarnation with absolute precision. Since Manichaeism stipulated that divine Light could not mix with intrinsically evil matter, the idea of God truly assuming human flesh was impossible within their framework. This required them to embrace the ancient heresy of Docetism.

Docetism: The Illusion of Humanity

Docetism, derived from the Greek word dokesis (“appearance” or “semblance”), taught that Christ only “appeared” or “seemed” to be a man, or that he possessed only the semblance of a human body. Manichaeans, as documented in their conflicts with Augustine, rejected the belief that the Son of God was born of a woman. They reinterpreted scriptural cornerstone passages, such as “The Word became flesh,” to mean that the Logos merely assumed a temporary disguise, like putting on a garment. This theological maneuvering preserved the radical divine transcendence but completely undermined Christ’s solidarity with humanity and the efficacy of His sacrifice.

This Docetist rejection of Christ’s material reality was part of a larger Manichaean rejection of the authoritative Scriptural canon. They “rejected the whole of the Old Testament,” viewing the God of creation (identified as the evil principle) as fundamentally distinct from the God of Light. They admitted only portions of the New Testament that suited their doctrines, notably rejecting the Acts of the Apostles because it testified to the historical descent of the Holy Ghost. Augustine was therefore compelled to defend the coherence and continuity of divine revelation found in both the Old and New Testaments against these impious fables.

The Unwavering Dogma of the Hypostatic Union

The Catholic Church’s response, rooted in the affirmation of the Incarnation (the Hypostatic Union), is the central bulwark against Docetism and all forms of spiritualised heresy. The doctrine affirms the essential truth that salvation is accomplished through the real humanity of Jesus Christ. The reality of Christ’s human nature, His birth, life, suffering, and death, is non-negotiable, emphasising several key theological points:

- Affirmation of Matter: The Incarnation validates the inherent value of the material world and the goodness of the human body, directly countering the Manichaean pessimism.

- Redemption through Suffering: The reality of Christ’s physical suffering and death is essential for the redemption of humanity. If Christ only “seemed” to suffer, the redemption accomplished on the cross is illusory.

- Holistic Salvation: Manichaeism aims for the mere escape of the light/soul from the prison of the darkness/body. Catholicism, through the Incarnation and the promised resurrection of the body, offers a holistic redemption that includes both soul and matter, restoring the human person to its intended dignity.

Ethical and Sacramental Distortion

The Manichaean view of evil matter also corrupted its ethical system and negated the Church’s sacramental life. The Manichaean population was divided into the Electi (the chosen) and the Auditores (the hearers). The Electi, who aimed for immediate escape from the material world, were bound by extreme ascetic demands: renunciation of earthly property, avoidance of industrial pursuits, enforced celibacy, and abstinence from any sensual gratification.

Critically, Manichaean ethics demanded the avoidance of reproduction because, in their view, procreation “makes a bad situation worse, embedding the light into more and more evil matter”. This view stands in radical opposition to the Catholic teaching on the sanctity of the body and the goodness of creation, which insists on the holiness of marriage and uses the analogy of Christ and the Church (Ephesians 5) to illustrate its divine significance.

The affirmation of the real Incarnation is the foundation of the Catholic sacramental economy. If the Word truly became flesh, then material elements, water in baptism, oil in anointing, bread and wine in the Eucharist, can serve as true conduits for divine grace. Manichaeism, by denying the spiritual potential of matter, is intrinsically anti-sacramental.

Key Catholic Objections to Manichaeism

The Catholic Church’s rejection of Manichaeism is rooted in its violations of fundamental dogma:

- Evil as Positive Substance: This view violates the Omnipotence and Monism of God, as well as the Goodness of Creation. The theological consequence is that God is not sovereign, and Creation is fundamentally flawed.

- Docetism (Apparent Humanity of Christ): This denies the Reality of the Incarnation (Hypostatic Union). The consequence is that it undermines the reality of the Passion and Resurrection, thereby voiding redemption.

- Rejection of the Old Testament: This violates the Unity of Divine Revelation, denying the Continuity of Salvation History. The consequence is that it separates the Creator God (the evil principle) from the Redeemer God.

- Rejection of Marriage/Procreation: This violates the Sanctity of the Body and the Sacrament of Matrimony. The consequence is that it reduces the human body to a disposable prison and denies the goodness affirmed in Genesis 1:28.

V. The Church’s Historical Response: Condemnation and Continuity

The Church’s struggle against Manichaeism was pervasive, beginning in the Patristic Age and extending through the Middle Ages. Due to its structural coherence and organised nature, Manichaeism was not a fleeting sect but a durable rival that required consistent defense by the Roman state and the Christian Church. This relentless persecution resulted in its virtual disappearance from Roman lands by the end of the sixth century.

Patristic Condemnation and Papal Vigilance

In the West, decisive condemnations came from leading bishops. Pope Leo the Great (c. 444 AD) actively investigated Manichaean adherents who had settled in Rome after being driven out of North Africa by the Vandals. Leo’s letters detailed the results of a senate tribunal over which he presided, issuing rigorous warnings to the Italian bishops about the insidious nature of the Manichaean communities.

Pope Leo’s extensive documentation of Manichaeism is highly instructive regarding the consequences of its metaphysics on practical ethics. Leo specifically accused the Manichaean Electi of sexual immorality. While the core Manichaean doctrine imposed extreme asceticism and celibacy upon its highest adherents , the philosophical denial of the intrinsic value of the body could logically lead to two dangerous extremes: either fanatical, life-denying self-mortification or, paradoxically, antinomian excess. If the body and matter are irredeemably evil and irrelevant to the salvation of the trapped soul, physical actions might be deemed morally indifferent, potentially allowing for the ritual sexual intercourse that Leo’s letters alleged was practiced by some of the Elect in Rome. This historical episode illustrates the danger inherent in adopting a dualistic framework: it separates theology from charity and morality from the physical reality of the human person.

The Medieval Resurgence: Neo-Manichaean Sects

The dualistic temptation proved to be a perennial fixture in Christian history. Even after formal Manichaeism faded in the West, teachings bearing strong structural and doctrinal resemblances resurfaced in Medieval Europe. These movements, often designated as “neo-Manichaean sects” by contemporary clerics, included the Paulicians in Armenia (7th century), the Bogomilists in Bulgaria (10th century), and most famously, the Cathari or Albigensians in Southern France (12th century).

Although modern scholarship questions the historical certainty of a direct, uninterrupted lineage of transmission from Mani to the Cathars, noting that the dualistic mindset itself is a persistent human spiritual impulse, the doctrinal similarities are undeniable. The Bogomils, for instance, were clearly influenced by older heresies like Manichaeism and Paulicianism, which emphasised extreme dualism. The Cathars similarly preached a rigid dualistic faith, radically rejecting the material world and, consequently, the sacraments of the Catholic Church.

The Church regarded these resurgent heresies as a direct and grave threat to both theological orthodoxy and civil order. The response was institutional and firm. In 1184, Pope Lucius III, in collaboration with Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa, issued the papal bull Ad Abolendam at the Synod of Verona. This decree explicitly condemned the Cathars and Waldensians as heretics, anathematising them and exhorting secular rulers to punish adherents severely. This act was a pivotal moment in consolidating the power of the institutional Church against internal dissent, laying the essential groundwork for later campaigns, including the Albigensian Crusade. The persistent reappearance of dualism across centuries confirms that it is a fundamental, recurring spiritual temptation that requires perpetual vigilance from the Church.

VI. Conclusion: The Contemporary Temptation of Functional Dualism

Manichaeism is not merely a footnote in Patristic history; its fundamental philosophical error, the splitting of reality into two co-equal, warring substances, remains a powerful spiritual temptation, manifest today in psychological and ideological forms that often mimic the ancient heresy.

The Shadow of Crypto-Manichaeism

Even the great champion of Catholic Monism, St. Augustine, serves as a testament to the persistent pull of dualistic thinking. Modern scholars have long analysed the potential crypto-Manichaean influences in Augustine’s later theological development. These influences are not borrowings of formal doctrine, but rather a subtle residue, manifesting as a general mood of pessimism regarding human nature, a degree of hostility toward the flesh and sexual activity, and the development of severe views on divine grace and human freedom. This phenomenon demonstrates that the war against Mani’s influence is not solely external; it is a battle for the wholeness of the Catholic mind. Even when the formal doctrine of privatio boni is affirmed, an unwarranted, visceral fear or contempt for the body or the material world can linger, a functional dualism that replaces metaphysical truth with psychological bias.

The Moral Dualism of Modern Conflict

The most pervasive modern echo of Manichaeism is found in the sphere of moral and ideological polarisation. When theological concepts are divorced from charity and placed in the service of partisan conflict, the temptation is strong to divide the world into clean, simple categories of absolute good and absolute evil. This mirrors Mani’s vision of an eternal, external conflict between Light and Darkness.

The contemporary magisterium has specifically addressed this danger. Pope Francis has criticised the tendency toward a “Manichaean worldview that separates people into two camps, the one good and the other evil,” noting its manifestation in overly rigid or politically motivated alliances within the religious landscape. This functional dualism replaces the essential messiness of the human condition, the complex interaction of grace and sin, good and defect, with a convenient but ultimately heretical categorisation.

Catholic theology demands a profoundly complex and balanced worldview that rejects all forms of radical dualism:

- Theistic Monism: God is the singular, absolute, sovereign good and the Creator of all being.

- Goodness of Creation: The material world, including the human body, is inherently good, having been created by God and affirmed by the Incarnation.

- Sin as Defect: Evil is real and potent, yet it is a parasitic defect (privatio boni) resulting from the misuse of freedom, not an eternal, co-equal substance.

- Holistic Redemption: Salvation is accomplished through the true humanity of Christ, redeeming both soul and body, and culminating in the resurrection of the flesh.

The spiritual danger of this modern, functional dualism is that it substitutes the rigorous, internal spiritual battle, the constant struggle against one’s own deficiencies and the recognition of mixed motives in oneself and others, for a simplistic ideological war. To condemn ideological opponents as absolute “Darkness” is to deny the effects of divine grace active outside one’s immediate sphere and, crucially, to deny the reality of one’s own internal mixture of grace and sin. By seeking refuge in such stark, external divisions, the polarising mind inadvertently commits the perennial error of Mani, mirroring his cosmic struggle in the realm of human affairs. The enduring lesson of the Manichaean heresy, therefore, is the perpetual Catholic call to affirm the goodness of God’s entire creation, even when wrestling with its wounds.